Circle

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the shape and mathematical concept. For other uses, see Circle (disambiguation).

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2010) |

Circles are simple closed curves which divide the plane into two regions, an interior and an exterior. In everyday use, the term "circle" may be used interchangeably to refer to either the boundary of the figure, or to the whole figure including its interior; in strict technical usage, the circle is the former and the latter is called a disk.

A circle is a special ellipse in which the two foci are coincident and the eccentricity is 0. Circles are conic sections attained when a right circular cone is intersected with a plane perpendicular to the axis of the cone.

Contents[hide] |

Terminology

A circle's diameter is the length of a line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle and which passes through the centre. This is the largest distance between any two points on the circle. The diameter of a circle is twice the radius, or distance from the centre to the circle's boundary (circumference). The terms 'diameter' and 'radius' also refer to the line segments which fit these descriptions.A chord is a line segment whose endpoints lie on the circle. A diameter is the longest chord in a circle. A tangent to a circle is a straight line that touches the circle at a single point, while a secant is an extended chord: a straight line cutting the circle at two points.

An arc of a circle is any connected part of the circle's circumference. A sector is a region bounded by two radii and an arc lying between the radii, and a segment is a region bounded by a chord and an arc lying between the chord's endpoints.

History

The circle has been known since before the beginning of recorded history. Natural circles would have been observed, such as the Moon, Sun, and a short plant stalk blowing in the wind on sand, which forms a circle shape in the sand. The circle is the basis for the wheel, which, with related inventions such as gears, makes much of modern civilization possible. In mathematics, the study of the circle has helped inspire the development of geometry, astronomy, and calculus.

Early science, particularly geometry and astrology and astronomy, was connected to the divine for most medieval scholars, and many believed that there was something intrinsically "divine" or "perfect" that could be found in circles.[citation needed]

Some highlights in the history of the circle are:

- 1700 BC – The Rhind papyrus gives a method to find the area of a circular field. The result corresponds to 256/81 (3.16049...) as an approximate value of π.[1]

- 300 BC – Book 3 of Euclid's Elements deals with the properties of circles.

- In Plato's Seventh Letter there is a detailed definition and explanation of the circle. Plato explains the perfect circle, and how it is different from any drawing, words, definition or explanation.

- 1880 – Lindemann proves that π is transcendental, effectively settling the millennia-old problem of squaring the circle.[2]

Analytic results

Length of circumference

Further information: Pi

The ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter is π (pi), an irrational constant (approximately equal to 3.141592654). Thus the length of the circumference C is related to the radius r and diameter d by C = 2πr = πd.Area enclosed

Main article: Area of a disk

As proved by Archimedes, the area enclosed by a circle is π multiplied by the radius squared:The circle is the plane curve enclosing the maximum area for a given arc length. This relates the circle to a problem in the calculus of variations, namely the isoperimetric inequality.

Equations

Cartesian coordinates

In an x-y Cartesian coordinate system, the circle with centre coordinates (a, b) and radius r is the set of all points (x, y) such thatIn homogeneous coordinates each conic section with equation of a circle is of the form

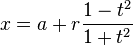

Polar coordinates

In polar coordinates the equation of a circle is:- r = 2acos(θ − φ).

,

,

Complex plane

In the complex plane, a circle with a centre at c and radius (r) has the equation . In parametric form this can be written z = reit + c.

. In parametric form this can be written z = reit + c.The slightly generalised equation

for real p, q and complex g is sometimes called a generalised circle. This becomes the above equation for a circle with

for real p, q and complex g is sometimes called a generalised circle. This becomes the above equation for a circle with  , since

, since  . Not all generalised circles are actually circles: a generalised circle is either a (true) circle or a line.

. Not all generalised circles are actually circles: a generalised circle is either a (true) circle or a line.Tangent lines

Main article: Tangent lines to circles

The tangent line through a point P on the circle is perpendicular to the diameter passing through P. If P = (x1, y1) and the circle has centre (a, b) and radius r, then the tangent line is perpendicular to the line from (a, b) to (x1, y1), so it has the form (x1−a)x+(y1−b)y = c. Evaluating at (x1, y1) determines the value of c and the result is that the equation of the tangent is- (x1 − a)x + (y1 − b)y = (x1 − a)x1 + (y1 − b)y1

- (x1 − a)(x − a) + (y1 − b)(y − b) = r2.

.

.

When the centre of the circle is at the origin then the equation of the tangent line becomes

- x1x + y1y = r2,

.

.

Properties

- The circle is the shape with the largest area for a given length of perimeter. (See Isoperimetric inequality.)

- The circle is a highly symmetric shape: every line through the centre forms a line of reflection symmetry and it has rotational symmetry around the centre for every angle. Its symmetry group is the orthogonal group O(2,R). The group of rotations alone is the circle group T.

- All circles are similar.

- A circle's circumference and radius are proportional.

- The area enclosed and the square of its radius are proportional.

- The circle which is centred at the origin with radius 1 is called the unit circle.

- Thought of as a great circle of the unit sphere, it becomes the Riemannian circle.

- Through any three points, not all on the same line, there lies a unique circle. In Cartesian coordinates, it is possible to give explicit formulae for the coordinates of the centre of the circle and the radius in terms of the coordinates of the three given points. See circumcircle.

Chord

- Chords are equidistant from the centre of a circle if and only if they are equal in length.

- The perpendicular bisector of a chord passes through the centre of a circle; equivalent statements stemming from the uniqueness of the perpendicular bisector:

- A perpendicular line from the centre of a circle bisects the chord.

- The line segment (circular segment) through the centre bisecting a chord is perpendicular to the chord.

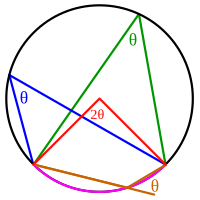

- If a central angle and an inscribed angle of a circle are subtended by the same chord and on the same side of the chord, then the central angle is twice the inscribed angle.

- If two angles are inscribed on the same chord and on the same side of the chord, then they are equal.

- If two angles are inscribed on the same chord and on opposite sides of the chord, then they are supplemental.

- For a cyclic quadrilateral, the exterior angle is equal to the interior opposite angle.

- An inscribed angle subtended by a diameter is a right angle (see Thales' theorem).

- The diameter is the longest chord of the circle.

- If the intersection of any two chords divides one chord into lengths a and b and divides the other chord into lengths c and d, then ab = cd.

- If the intersection of any two perpendicular chords divides one chord into lengths a and b and divides the other chord into lengths c and d, then a2 + b2 + c2 + d2 equals the square of the diameter.

- The distance from a point on the circle to a given chord times the diameter of the circle equals the product of the distances from the point to the ends of the chord.[3]:p.71

Sagitta

- The sagitta (also known as the versine) is a line segment drawn perpendicular to a chord, between the midpoint of that chord and the arc of the circle.

- Given the length y of a chord, and the length x of the sagitta, the Pythagorean theorem can be used to calculate the radius of the unique circle which will fit around the two lines:

Tangent

- The line perpendicular drawn to a radius through the end point of the radius is a tangent to the circle.

- A line drawn perpendicular to a tangent through the point of contact with a circle passes through the centre of the circle.

- Two tangents can always be drawn to a circle from any point outside the circle, and these tangents are equal in length.

- If a tangent at A and a tangent at B intersect at the exterior point P, then denoting the center as O, the angles ∠BOA and ∠BPA are supplementary.

- If AD is tangent to the circle at A and if AQ is a chord of the circle, then ∠DAQ =

arc(AQ).

arc(AQ).

Theorems

See also: Power of a point

- The chord theorem states that if two chords, CD and EB, intersect at A, then CA×DA = EA×BA.

- If a tangent from an external point D meets the circle at C and a secant from the external point D meets the circle at G and E respectively, then DC2 = DG×DE. (Tangent-secant theorem.)

- If two secants, DG and DE, also cut the circle at H and F respectively, then DH×DG = DF×DE. (Corollary of the tangent-secant theorem.)

- The angle between a tangent and chord is equal to one half the subtended angle on the opposite side of the chord (Tangent Chord Angle).

- If the angle subtended by the chord at the centre is 90 degrees then l = √2 × r, where l is the length of the chord and r is the radius of the circle.

- If two secants are inscribed in the circle as shown at right, then the measurement of angle A is equal to one half the difference of the measurements of the enclosed arcs (DE and BC). This is the secant-secant theorem.

Inscribed angles

See also: Inscribed angle theorem

An inscribed angle (examples are the blue and green angles in the figure) is exactly half the corresponding central angle (red). Hence, all inscribed angles that subtend the same arc (pink) are equal. Angles inscribed on the arc (brown) are supplementary. In particular, every inscribed angle that subtends a diameter is a right angle (since the central angle is 180 degrees).Apollonius circle

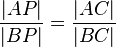

Apollonius of Perga showed that a circle may also be defined as the set of points in a plane having a constant ratio (other than 1) of distances to two fixed foci, A and B. (The set of points where the distances are equal is the perpendicular bisector of A and B, a line.) That circle is sometimes said to be drawn about two points[4].The proof is as follows. A line segment PC bisects the interior angle APB, since the segments are similar:

, the angle CPD is exactly

, the angle CPD is exactly  , i.e., a right angle. The set of points P that form a right angle with a given line segment CD form a circle, of which CD is the diameter.

, i.e., a right angle. The set of points P that form a right angle with a given line segment CD form a circle, of which CD is the diameter.Cross-ratios

A closely related property of circles involves the geometry of the cross-ratio of points in the complex plane. If A, B, and C are as above, then the Apollonius circle for these three points is the collection of points P for which the absolute value of the cross-ratio is equal to one:Generalized circles

See also: Generalized circle

If C is the midpoint of the segment AB, then the collection of points P satisfying the Apollonius condition (1)

(1)

Thus, if A, B, and C are given distinct points in the plane, then the locus of points P satisfying (1) is called a generalized circle. It may either be a true circle or a line. In this sense a line is a generalized circle of infinite radius.

See also

Notes

- ^ Chronology for 30000 BC to 500 BC

- ^ Squaring the circle

- ^ Johnson, Roger A., Advanced Euclidean Geometry, Dover Publ., 2007.

- ^ Harkness, James (1898). Introduction to the theory of analytic functions. London, New York: Macmillan and Co.. pp. 30. http://dlxs2.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=math;idno=01680002.

References

- Pedoe, Dan (1988). Geometry: a comprehensive course. Dover.

- "Circle" in The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Circle geometry |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Circles |

- Circle (PlanetMath.org website)

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Circle" from MathWorld.

- Interactive Java applets for the properties of and elementary constructions involving circles.

- Interactive Standard Form Equation of Circle Click and drag points to see standard form equation in action

- Munching on Circles at cut-the-knot

- Ron Blond homepage - interactive applets

- calculate circumference and area with your own values

- MathAce's Circle article - has a good in-depth explanation of unit circles and transforming circular equations.

- Google Maps Circle Overlay Lets you add a circle to Google Maps

![|[A,B;C,P]| = 1.\](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/9/e/0/9e035e9d62f94ddf78be8760a6482aab.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment